To paraphrase Tinto Brass, there’s paprica and there’s Paprika. Italy’s favourite eroticist informed us that not all red powder is the same, and so it is with Giro stages. They all have bike riders, but a flat stage can never offer quite the same spice as a mountainous one. Unless, of course, it’s the stage to Győr...

What could possibly go wrong on the flat roads of the Puszta, between decadent rows of sunflowers and the curious gaze of wild horses? What could derail the first bunch sprint of a Giro d’Italia still to set foot on Italian soil? If the answer is to be found in a broken frame leant against a guard rail, the question is whether Peter Sagan’s Giro is finished after just two days. Even Elia Viviani, the stage winner who grew up with him at Liquigas, was in no mood to celebrate – he was more concerned for the wellbeing of his former team mate. Given the way it played out, it would have been better after all had the break stayed away. Best would be to rewind the whole thing, start again from scratch and find an altogether different conclusion. Less breath taking perhaps, but also less traumatic.

While we journalists contemplated the statue of Lajos Kossuth in Heroes’ Square, idly comparing it to the bust in downtown Turin, ten of them wriggled free. They hadn’t left the decaying tower blocks of suburban Budapest and yet here they were, martyrs once more to their instinct and to their sponsors. They knew – just as everyone knew – that when finally the gruppo roused itself from its torpor, such resistance as they could offer would be futile. At Tata, more or less half-distance, they’d fifteen minutes. If anything was more predictable than the break, it was its constituents. Amongst them were guys from teams whose entire budget for the season would (more or less) cover Sagan’s wages. The likes of Manuel Belletti; Androni’s veteran was the winner, no less, of the 2018 Tour of Hungary. Last year he won the stage to Eszergom or, as the toponym pedants would have it, Strigonio. In the Androni team car, a pensive Gianni Savio caressed his whiskers. Since discovering Egan Bernal, Savio seems to have shed 20 years. To his ubiquitous enthusiasm he’s added a dash of pride, and it radiates from the pre-, -mid and post-stage anecdotes which are his stock-in-trade.

Gianni’s smile stiffened when UAE Emirates, Bora and Bahrain set to reeling them in. The Emirates guys, with their white jerseys and red collars, bring to mind my first Hungarian experience, back in 1987. It was a school trip, the students of the Zanella Middle School in Padua crammed into a bus and despatched, noisily and urgently, to Szeged. Of course our coach bore precisely no relation to the five-star wonders which host 21st century bike riders and nor, truth be told, did the context. This was the cold war and so, following a 16-hour journey we presented ourselves at the ceremonial unmasking of the scholastic year. Amidst the various anthems we formed a disorderly Italian queue whilst our hosts, resplendent in the white shirts and red neckerchiefs of the Young Pioneers, lined up perfectly.

Who knows whether, in his previous life as an East German toddler, André Greipel wore the Young Pioneers outfit? (In point of fact who can know, with any degree of certitude, whether the mighty Greipel was ever a “toddler” at all?). Hamstrung by injury, Greipel was greatly missed in this, the first gallop. Perhaps had he been present things would have different. Maybe Cavendish wouldn’t have drifted towards the guard rail, and perhaps Sagan wouldn’t have tried to occupy a space which, objectively, didn’t exist. Momentarily it seemed we were watching a replay of the Tour stage to Vittel in 2017, except this time the roles were reversed. Thus, here it was the turn of the Slovak to fly, and to inadvertently take down both Arnaud Démare and Caleb Ewan. Each suffered flesh wounds, but nothing of consequence. This was the maelstrom from which the excellent Viviani emerged, and the jury confirmed his photo-finish win over Cavendish.

On days like these, however, the results are secondary to the medical report. This one was compiled several hours later, as Sagan emerged from the mobile X-Ray accompanied, as if in an old Cronenberg movie, by the inseparable Gabriele Ubaldi. Sagan’s right shoulder was bandaged: a dislocation. By way of reassurance, someone reminded him that Contador had actually won the 2015 Giro was a dislocated shoulder. Sagan told the guy that he “doesn’t have to win the Giro”, and that put a smile on everyone’s face. Then, as he made his way towards the sanctity of the team car, the questions came thick and fast; “What are the chances we’ll see you at the roll-out tomorrow?” “Does it hurt a lot?” “Might you abandon?” Sagan stopped, turned and, with that voice of his (the one that someone, sooner or later, will copy as a carton voiceover) replied, “I can ride a bike pretty well, hands or no hands…” The Giro rolls on.

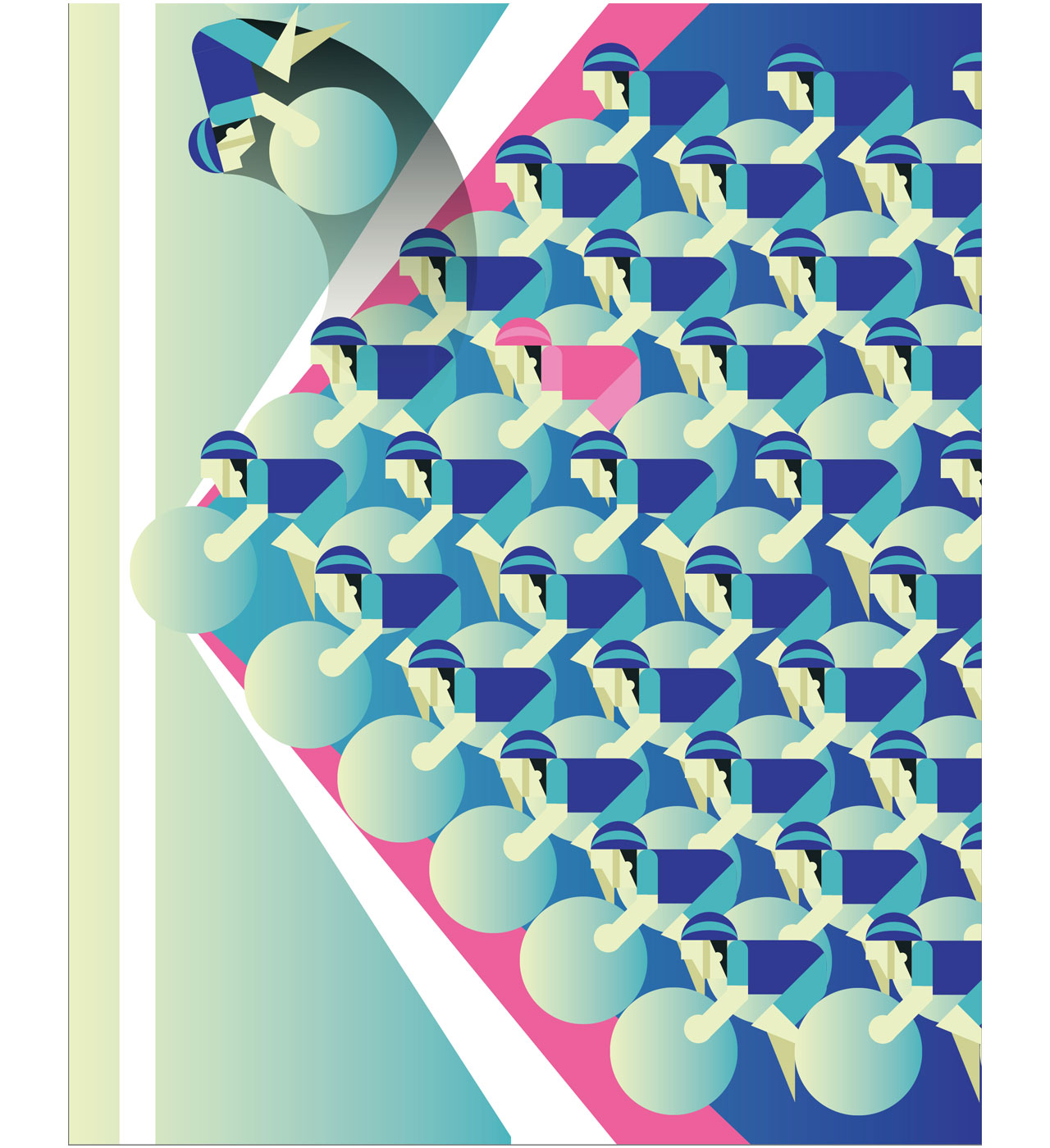

This jersey will be signed by the stage winner and auctioned for charity at the end of the Senzagiro. Design curated by Fergus Niland, Creative Director of Santini Cycling Wear, based on a design by the illustrator Francesco Poroli.

To view the stage and general standings and learn more about the Senzagiro project